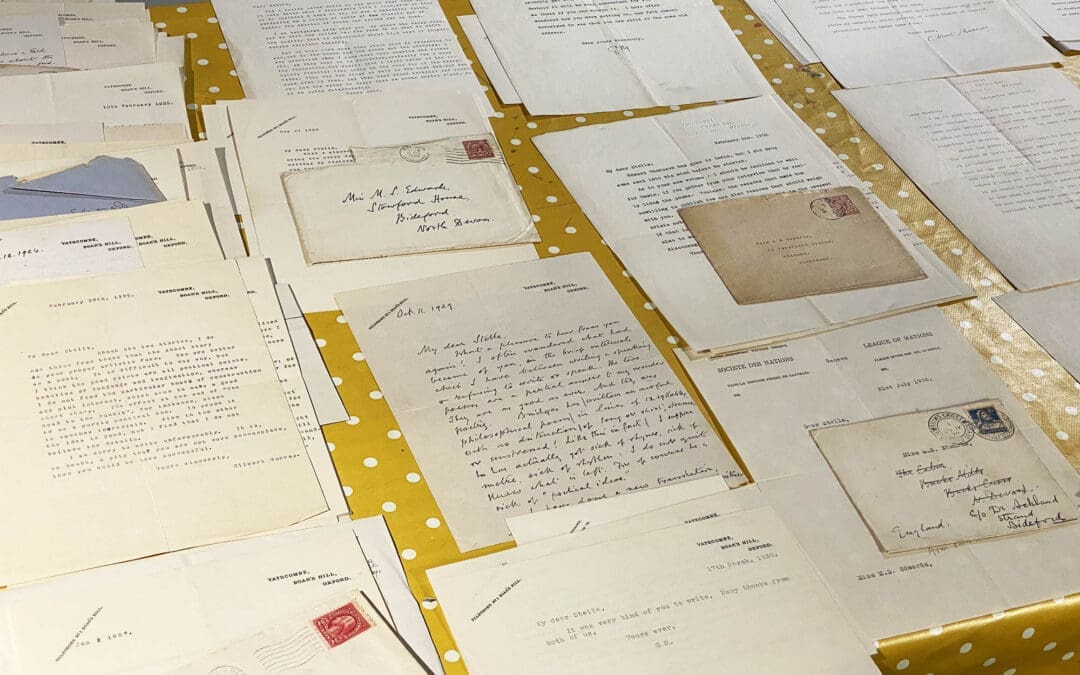

Mary Stella Edwards actively put together the Ackland and Edwards archive in the years after Judith Ackland died. But why? The two women weren’t well-known as artists, and Edwards’ final three books of poetry were published very late in her lifetime. Might this be the first clue? Mary Stella spent the first years after Judith’s death arranging memorial exhibitions and donating her works to galleries and museums. She wanted Judith’s work to be known and appreciated, and even managed to get some television coverage. (Mary Stella Edwards would have conquered all on social media, I am sure.) Perhaps while promoting Judith’s work, her own began to gain more recognition? By 1979, as she tells May Sarton in a letter, seven galleries / museums had collected Judith’s work, and five had collected hers.

Telling their story

The discovery of a letter from May Sarton, dated 9 November 1982, made me stop and think again. Sarton wrote: ‘Dear heart, I do not want you to die but I dearly want to read the book of letters and journals which will tell the moving story of you and Judith. I am so happy you felt you could do this and I feel sure it is right to do it. Any great love such as yours was adds something to the grace of humanity itself and must give us all courage and hope.’

The letter told me two things. By 1982 Mary Stella wants to tell their story – so the archive is not just about preserving their work. Secondly, she wants this story to be told after she has died. It also explains the presence of the pencilled lines down the margins of her journals, with extra notes such as “Quote!” underlined in red on scrap paper bookmarks throughout!

What did Judith think?

In many ways Judith is a shadowy figure in the archive. There is just one journal of hers, to the 20+ of Mary Stella’s for example. At the moment, I mainly know her through Mary Stella’s words. And the following letter, read a couple of months ago, is an example of this process in action. Here is the typed note in full:

‘21.10.1973, Staines

Judith’s attitude (though she was always reticent) had greatly changed during the just over 33 years that followed, from her opinion on the private nature of letters & poems, when considering the likely comments of long ago. Even more so of late, as we discussed this, I think in the winter of 1970, & she felt that the letters would truly tell “our story” (though of course editing is needed, for them & for the diaries as well) & also give most vividly the feel of the times.

But perhaps the right time has still not quite come. There is no “label” that could enclose all the kinds of love we felt for each other – the starry heights, the simple joy of “being” together, & all the deep happy relationships between…

She saw that they should be published when the time came.

MSE’

The phrases that stood out to me were ‘the likely comments of long ago’ and ‘There is no “label” that could enclose all the kinds of love we felt for each other’. Notice that this is something they discussed for 33 years! Layers of nuance are being expressed here, which I am still digesting. I am beginning to learn that a 2024 understanding of identity is very different to the understanding of someone born in the Victorian era.

‘Experienced editing is required’

What kind of editing does Edwards imagine will need to be done to the diaries and letters? Given her wish to tell ‘their story’ I thought she just meant making them more succinct! But another note, quoting a passage from Julien Green’s 1928-1957 diary, suggests another interpretation. The quote from Green reads:

‘I would very much like these pages to be published. I think it will be possible someday, because people will then be able to stand the truth better than we do in 1950, but I may be mistaken; one should always credit human beings with great stupidity. In the world’s present state, this diary would dismay the very people it is made for. It is nevertheless my best book – (I am talking of course about the unexpurgated text)’

Julien Green

A handwritten note from Mary Stella Edwards at bottom of the note reads: ‘In the case of my Diaries a great deal of selection & experienced editing is required.’

I understand this to mean that she did not want her ‘unexpurgated texts’ released to the world! Mary Stella was not to know this, but when Green’s unabridged diaries were finally published in 2019, they contained a great deal more than descriptions of his relationships with other men…

In fact, the Ackland and Edwards archive contains no intimate details of their lives together. It seems likely that Mary Stella did a little editing herself before she died! But it doesn’t need to: Edwards’ poems openly tell the reader everything about her and Judith’s immense love for one another. (Her love poems are quite extraordinary.) Therefore the archive does indeed tell their story, and in so doing adds depth and context to their work.

Judith and Mary

I’ll conclude with two letters to the American poet John Hall Wheelock from the 1970s, which really helped me to understand why Mary Stella Edwards spent so much time creating the Ackland and Edwards Trust, and assembling the archive.

In October 1977 Edwards wrote to Wheelock:

‘How wonderful to have your joint letter – I am so grateful for its being written, & for the lovely words about Judith & me that have a prophetic sound. It makes me think of one of many of the Wordsworth books read lately, – ‘William and Dorothy’ – it could not possibly be any other people; & I thought suppose one day it was “Judith and Mary” with that same certainty…’

Before that, in June 1974 she wrote to Wheelock:

‘This happened – rejections – even when Gilbert Murray was practically “agenting” for me. His belief in my work never slackened, during a friendship of 37 years. & predicted that I should be famous by the time I was 60!! Already 16 years out on I no longer have ambition, save that Judith’s & my names should be remembered together.’

In the next blogpost: Letters from Gilbert Murray

Previous Blogpost: The Dark Pool