Early in my PhD research I wondered who might play Mary Stella Edwards and Judith Ackland in a film about their lives. After much thought and debate with the archive volunteers, we came up with Haydn Gwynne to play Judith and Helen McCrory to play Mary Stella. The obvious director would be Jane Campion – and that would be lovely – but I’d rather see the movie directed by Sofia Coppola. What genre though? I considered artist biopic, or historical drama but neither seemed to quite fit. “It’s obvious” said Warren Collum, Collections Manager at the Burton. “It’s a love story.”

What kind of love story?

He’s right, of course! But what kind of love story? The temptation to focus on Mary Stella and Judith’s lives through an LGBTQ+ lens is enormous. After all, it’s a joy to find two women from the last century who were in love with one another for decades. They successfully built a creative life together, and from the late 1940s lived together too. But – and this is a huge “but” – it does not appear to be the way that Mary Stella Edwards and Judith Ackland wanted to be remembered.

The archive was carefully curated by Mary Stella Edwards after Judith Ackland’s death. See Why does the archive exist for my earlier thoughts on this. Sometimes it feels as though she’s not-so-subtly directing my research. For example, I have already mentioned the bookmarks and notes in the journals pointing to certain passages, with various messages underlined in red pencil. I know from the later journals that she burnt huge quantities of letters, so have come to believe that anything I find in the archive is something that she actively wanted to be there.

An awkward misunderstanding

So it was that I came across a seemingly innocuous handwritten fan letter that Mary Stella received from Jill Putnam in 1981. Jill writes obliquely of her and her partner Heather’s “special interest” in Edwards and Ackland. She wrote “we feel we have much in common with you both”. And, “We have lived together now for eleven years and would consider ourselves very lucky if we have as long together as you did.” Edwards’ response (not in the archive) was to ‘misread’ Jill’s name as “Jim”.

Jill tries again – a typed letter this time: “…perhaps you might care to read it [her original letter] again in the light of its author being a woman. I feel that you will have missed half of its meaning – having read it as from a man…” Mary Stella does apologise for mis-reading Jill’s name. But she refuses to admit that she could read Jill’s letter in any other way, stating: “No-one has ‘much in common’ with us – unique as the North Star as seen from the Cabin doorway; or perhaps the Northern Lights, as their display had folds & levels.” Ouch.

This is not the only example of Mary Stella Edwards seemingly ‘misunderstanding’ something that someone is trying to write about nature of her and Judith’s relationship. But it is the most pointed. The film of Mary Stella Edwards’ and Judith Ackland’s lives together would be a love story… However, one of the things that would make it such an interesting film is that this love is so difficult to categorise.

The problems with labels

On 21 October 1973 Edwards wrote of their relationship: “There is no ‘label’ that could enclose all the kinds of love we felt for each other – the starry heights, the simple joy of ‘being’ together, & all the deep happy relationships between…” (See Why does the archive exist for the full quote.)

Her friend, the American poet and writer May Sarton objected strongly to being described as a ‘lesbian writer’ on the basis that love was love – the loved person’s gender should not matter. I suspect that Mary Stella and Judith felt the same way, and interviews with people who knew both women have revealed that they were intensely private people. And yet… and yet… in 1974 she wrote in a letter to John Hall Wheelock that her one remaining ambition is for Judith’s and her names to be “remembered together”. Sometimes I feel that my research is going round in circles!

“Judith and Mary”

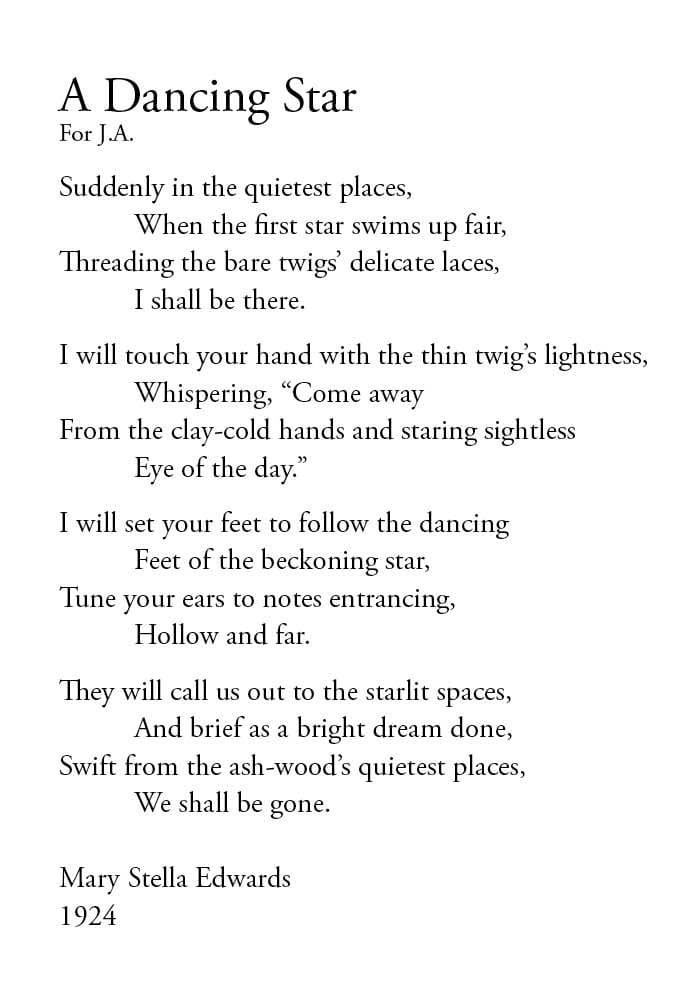

Up till now, Judith has remained a shadowy figure for me – see Finding Judith Ackland in the archive for my earlier thoughts on that. However, since I have been reading her and Mary Stella’s letters to one another I have come to realise just how immensely important Judith was to Mary Stella’s work, and vice versa. For example, I had thought that Gilbert Murray had influenced Edwards’ work (my inner feminist is rather ashamed to admit this) and was quite surprised that aside from a few suggestions he had very little impact on her actual work. The letters from Judith tell quite a different story! I’ll write about this more in a future blogpost. For now it’s enough to say that as Edwards’ first reader (and the subject of many of her poems) Judith contributed a great deal to her evolution as a poet.

At last, I think I finally understand Edwards’ October 1977 letter to John Hall Wheelock: “I am so grateful … for the lovely words about Judith & me that have a prophetic sound. It makes me think of one of many of the Wordsworth books read lately, – ‘William and Dorothy’ – it could not possibly be any other people; & I thought suppose one day it was ‘Judith and Mary’ with that same certainty…”

Dorothy was William Wordsworth’s sister, who had an immense impact on his work, and they lived together for most of their adult lives, even as William married and had children.

I have begun to think of Mary Stella Edwards and Judith Ackland through the lens of ‘Lichenism’ – a way of exploring their relationship as a symbiotic and composite way of living creatively in a sometimes hostile world. “Folds & levels” indeed, “folds & levels”!

Rachel Marsh

Previous blogpost: Mary Stella Edwards’ school days