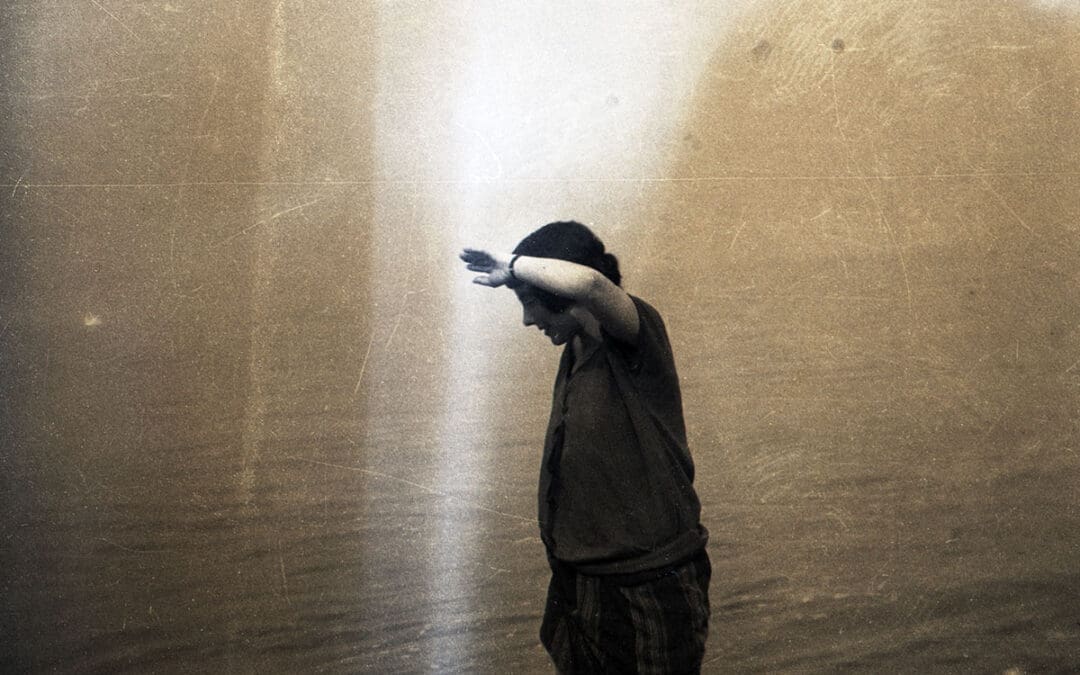

The photo above of Mary Stella Edwards is my favourite one of her in the archive. It’s a miss-shot really. Perhaps there was a light leak in the camera. But it shows – perhaps better than words can describe – how Mary Stella Edwards wrote poetry.

Queen of enjambment

Edwards rarely describes her poetry writing process in her journals, which I find both surprising and frustrating. Her poems are traditional in form, often using iambic pentameter (five beats to a line) though with subtle variations to great effect. Her work usually rhymes, but not in a way you immediately notice. She is the Queen of ‘enjambment’ – where one line carries on to the next – which she uses for pace and emphasis. I’ve discovered that her poems work best when read out loud. They are lyric poems, written to be heard more than read. They go down well at poetry readings. In short, her poetry is skilfully written and must have taken a great deal of time and thought.

“Presented to me from the air”

Therefore, I was astonished when I found Edwards’ description of her writing process in her 1959 journal:

22 February 1959: In the evening a poem that has been hovering started on paper – 10 lines. Very strange, as it has no known springs – ‘the tongues of the dead…’

A few days later.

6 March 1959: In the night – about 3 o’clock – I wrote the second half the poem, now all ‘there’, but perhaps some working over needed, though I think the final lines – which ‘came’ after a stoppage can stand. It was nearly all presented to me from the air in the true way, & J[udith] thinks it is very good; & I too that it is among my best.

I found a bookmark in the journal with a pencil note: “QUOTE The coming of the poem ‘Bone to Bone’”. This confirmed what I already knew. Bone to Bone is the final poem in A Truce with Time. It is peculiar and rather eerie. And as I reread the poem having just read the journal entries, the line “Speaks to the living from the decades dead” made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.

A poetry muse?

What to make of Edwards’ statement that this poem was “presented” to her “from the air” – in this “true way” of writing poetry? Especially when the poems themselves suggest hours of careful work. I am intrigued by her surprise at the content of the poem: “Very strange, as it has no known springs”. Her professional work as an artist and illustrator was careful, measured, and controlled. In contrast, Edwards’ poetry seems to be the place where she is most able to let go. Perhaps the place she is most able to be herself.

My current theory is that the poems ‘came’ to her in a similar way throughout her life, but the amount of “working over” (as she describes above) increased over time. In the previous blog, I described how Edwards’ wrote her 1924 poem ‘A Lament for Murdered Trees’ in 5 minutes flat, in a kind of “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” (as AE Housman described Wordsworth’s writing), without as far as I can tell, any reworking at all. If she believes that poems are delivered, as if by a Muse, this would explain why she seems quite happy to agree with the publisher Stanley Unwin’s view in 1924 that “my chief fault is lack of fundamental brainwork” (Journal: 19.06.1924), even going on to write that family friend Edmond Kapp had “accused” her of the same thing.

Doing enough ‘carpentry’

By the 1950s she was doing more reworking of her poems. “I think I am now getting ‘sharper’;” she wrote to May Sarton in 1965. “Perhaps more mind, rather than lyric flow, goes into them.” She goes on to say that she would find it difficult to rework her poem Viewpoint. It had been written over ten years before “& has sort of hardened into rock”. However, she adds “I have sometimes been able to work on things older”.

In her 1975 correspondence with poet Mark Wild, she advises him to do a little more work on his poems before they are finished. She writes: “They must I think have been ‘given’ – 3 or 4 lines perhaps coming ‘from elsewhere’ – but having experienced this, you haven’t done quite enough ‘carpentry’ on them, which was said to be the effect Frances Cornford conveyed when it came to working on what had ‘come’.”

Edwards’ 1974 poem “In Quires and Places Where They Sing” is a witty take on writing poetry as though she both the architect and builder of a “church-like place”, using words and paper as her building material. But the building is not going well, and she laments “The words discarded and the new ones tried / On reams and quires now ashes”. But the work is “not yet fit” so “counting not the waste, or time’s vast sum, / I build again with paper for my stone.”

AE Housman’s The Name and Nature of Poetry

By the early 70s Mary Stella Edwards was telling her correspondents about Housman’s essay “The Name and Nature of Poetry”, which Judith had given her. In it, Housman describes writing poetry as being “less an active than a passive and involuntary process”. Judith said that the essay explained “exactly” the process of writing poetry as Mary Stella had described it to her. I’ll close this blogpost with the relevant part of the essay – though I doubt that Mary Stella Edwards’ own poetry writing process included the pint of beer.

Having drunk a pint of beer at luncheon – beer is a sedative to the brain, and my afternoons are the least intellectual portion of my life – I would go out for a walk of two or three hours. As I went along, thinking of nothing in particular, only looking at things around me and following the progress of the seasons, there would flow into my mind, with sudden and unaccountable emotion, sometimes a line or two of verse, sometimes a whole stanza at once, accompanied, not preceded, by a vague notion of the poem which they were destined to form part of. Then there would usually be a lull of an hour or so, then perhaps the spring would bubble up again. I say bubble up, because, so far as I could make out, the source of the suggestions thus proffered to the brain was an abyss which I have already had occasion to mention, the pit of the stomach. When I got home I wrote them down, leaving gaps, and hoping that further inspiration might be forthcoming another day. Sometimes it was, if I took my walks in a receptive and expectant frame of mind; but some- times the poem had to be taken in hand and completed by the brain, which was apt to be a matter of trouble and anxiety, involving trial and disappointment, and sometimes ending in failure. I happen to remember distinctly the genesis of the piece which stands last in my first volume. Two of the stanzas, I do not say which, came into my head, just as they are printed, while I was crossing the corner of Hampstead Heath between the Spaniard’s Inn and the footpath to Temple Fortune. A third stanza came with a little coaxing after tea. One more was needed, but it did not come: I had to turn to and compose it myself, and that was a laborious business. I wrote it thirteen times, and it was more than a twelvemonth before I got it right.

In the next blogpost: Finding Judith Ackland in the Archive

Previous blogpost: Lament for Murdered Trees, and a Curse on Evil Men