To me, Mary Stella Edwards’ first book of poetry is haunted by fairies and nature spirits. They aren’t obvious – so perhaps other readers might disagree. She never actually uses the word “fairy” – but they are implied in a kind of world-building that feels closely related to Walter de la Mare’s “The Listeners”. The poems evoke a feeling that’s half fairy tale, half dream-state. I love these early Edwards’ poems for their other-worldly connection to the natural world. She hears the voices of the streams and the stones, and gives agency to the sand on the beach.

Her journals however, contain too many fairies for my taste. The 1920s and 30s are full of descriptions of places that use the word ‘fairy’ as an adjective: fairy light, fairy view, fairy lake. I suspect reading these journals has affected the way I’ve read some of her early poems. I’ll be honest here… I am not a fan of fairy folk. They remind me of Victorian flower-fairy books – full of doe-eyed children with insect wings. Yuck. Leave those insects alone! However, the darker side of faery is a different matter altogether. There’s nothing twee about Alan Garner or Arthur Rackham.

A folkloric epiphany

In August, I had an epiphany about the faery world and what it might have meant to Mary Stella Edwards. I visited Green Hill Arts in Moretonhampstead, to see the Widdershins 3 exhibition. To my surprise, the artist Terri Windling had written quotes from writers, naturalists and folklorists all over the walls – under, between and sometimes around the artworks. Here are some of the quotes that particularly jumped off the wall at me:

‘The job of a storyteller is to speak the truth – but what we feel most deeply cannot be spoken in words. At this level only images connect. And so story becomes symbol, and symbol is myth’

– Alan Garner, writer

‘Folklore is the perfect second skin. From under its hide we can see all the shimmering, shadowy uncertainties of the world.’

– Jane Yolen, writer and folklorist

‘There are occasions when you can hear the mysterious language of the Earth, in water or coming through the trees, emanating from the mosses, seeping through the under currents of the soil, but you have to be willing to wait and receive.’

– John Hay, naturalist

‘I think in my heart I have always believed in fairies. Not fairies as seen in children’s picture books but Nature spirits whose life is part of the wind and the flowers and the trees. Born in the West Country and returning to it in middle life – how could I do anything else?’

– Elizabeth Goudge, writer

It was a real ‘huh!’ moment. Maybe it wasn’t about fairies at all. Perhaps Mary Stella Edwards found a way to frame her connection to the natural world through this folkloric realm? As a hypothesis it makes a lot of sense. The Celtic revival – a mash-up of nature spirits, ancient mythologies and folklore – fed her imagination. She read fairy tales throughout her childhood – and revisited them again and again throughout her adult life. She loved The Golden Bough by James Frazer – the source of her knowledge about the St John’s bonfires that Judith asked her about (see previous blogpost).

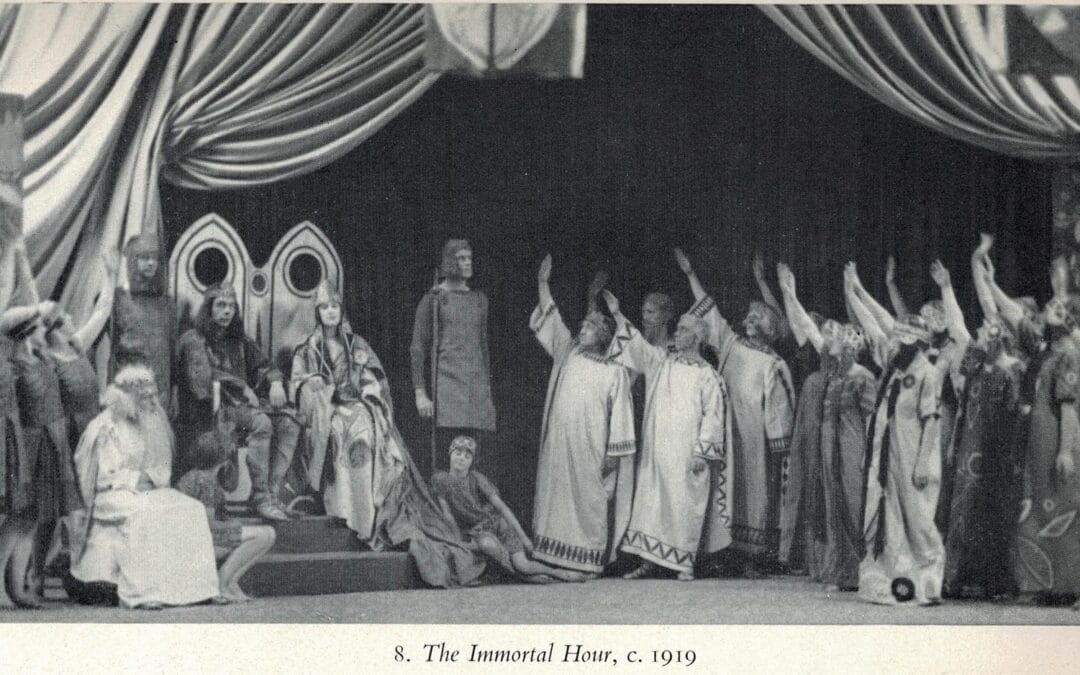

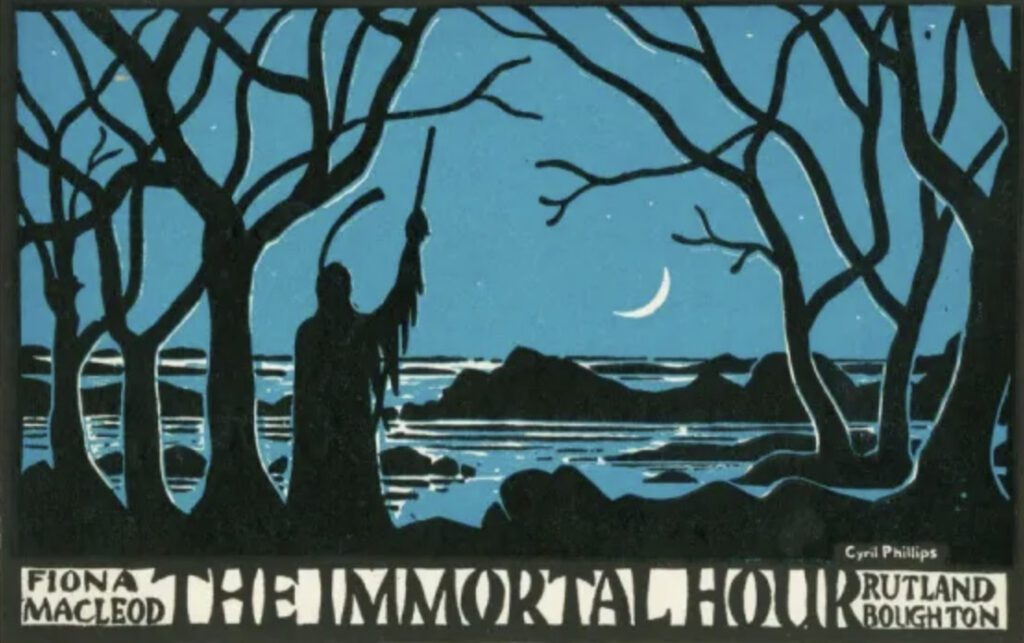

But the strongest evidence is her fascination with “The Immortal Hour” by Rutland Boughton. This was a faery opera adapted from the play by Fiona Macleod (aka William Sharp). The story was loosely based on the Irish legend of Etain and Eochaid. It was full of magic and sadness… and Mary Stella Edwards enjoyed both of those. Boughton studied folksongs from the Scottish Highlands before writing the score with its haunting songs. The recurring fairy song included the chorus line: ‘How beautiful they are, the lordly ones, who dwell in the hills, in the hollow hills’.

The importance of “The Immortal Hour”

My current theory is that “The Immortal Hour” gave Mary Stella Edwards the language to describe the deep connection she felt with the natural world when she was alone. It seems similar to that uncanny feeling one can have among standing stones or while walking down an ancient green lane… of hearing the feet of the ancient ancestors walking the same paths.

Back in August/September 1914, Edwards was on a family holiday in north Dartmoor. She was old enough to explore the area on her own, dreaming of druids and sacrifices at Scorhill stone circle, writing long essays about the beauty she saw from her bedroom window and at Fingle Bridge, and rescuing a baby hedgehog. Her descriptions are intense and very visual.

Looking back on this holiday, when she visited again in September 1925, she wrote in her journal: ‘We are again at Chagford, unseen since 1914 and this place where I was first conscious of Nature appealing to me in a new and vivid way …’.

I think Edwards went to see “The Immortal Hour” in 1922 – possibly more than once. She explains the importance of the opera to Judith in a letter from April 1925, writing: ‘If you think I talk overmuch, as at the beginning of this letter, of “The Immortal Hour” and all that it stands for, it is only because it translates into definite images – that everyone who has heard it can understand, – the feelings I had for long before that, but found difficulty in conveying in ordinary language.’

By chance, I transcribed this letter a week after seeing the Widdershins exhibition. It immediately reminded me of the Alan Garner quote above: “…what we feel most deeply cannot be spoken in words. At this level only images connect.”

Outcasts of the invisible world…

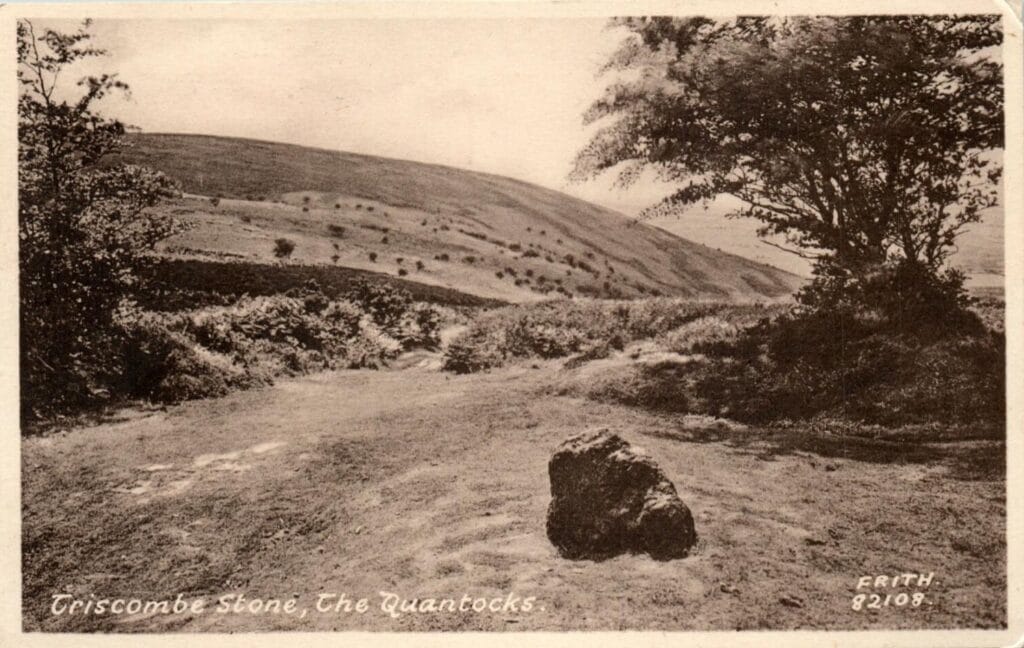

By 1926, I suspect that Edwards’ obsession with “The Immortal Hour” had become something of a family joke. In September, the family was on holiday again, this time in the Quantocks. On Wills Neck, the high and ancient ridgetop path – and before she learned its history – Edwards declaimed: ‘This place is full of awful and ancient voices, outcasts of the invisible world.’ At which, she recounted in her journal: ‘F[ather] began the mocking chorus from “The Immortal Hour”’!

As I came out of Green Hills Arts, I found three troupes of Morris dancers accompanied by a Bear wearing a crown of pheasant feathers, who played the drum or swayed in time to the music. It wasn’t quite faery, but it was certainly folkloric.

For more information on Boughton and “The Immortal Hour”, see: https://britishfairies.wordpress.com/2019/06/23/the-immortal-hour-avalon-opera-faerie/

Previous blog: Getting to know Judith Ackland